Munificent Mulberry

By Audrey Stallsmith

Now humble as the ripest mulberry

That will not hold the handling.

William Shakespeare, Coriolanus

Several years ago a weed sprang up too close to one of my hardy geraniums. Because the weed didn't come up easily and digging it out might harm the geranium, I fell into the lazy habit of cutting back the interloper instead. But it soon became apparent that the "weed" was actually a tree of some sort.

And all that drastic pruning didn't seem to faze it. This year, when I didn't get to it fast enough, the now bushy weed stood taller than me. So I posted a picture of the leaves online, and was informed that my "weed" was actually a mulberry tree.

I'd always wanted a mulberry, to help divert the birds from our cherries. I just didn't want it in the flower bed! So one damp day this fall I decided to tranplant the tree. To accomplish this feat, I had to dig up the geranium as well. But moving the mulberry itself proved more difficult.

After much digging, hacking, and straining, I discovered that mulberry roots have a peculiar orange flesh. And that trying to get them out will often result in your sitting sulkily on muddy ground, muttering to yourself! This proved to be more of a ripping out than a transplanting, so I'm not sure my mulberry will survive. Though I do have a sneaking suspicion that it will probably sprout again in the flower bed where I don't want it.

It is a pretty tree, however. And its official name morus derives from the Latin mora ("delay"), as mulberry puts off blooming until most threat of frost is behind it. Perhaps that's why the white type stands for "wisdom" in the Language of Flowers.

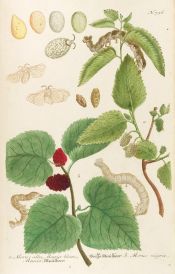

Especially revered in China, the white mulberry is essential to the production of silk. Silk worms feed on Morus alba leaves, and the threads of the fine fabric are harvested from the cocoons those larvae spin. Chinese legend holds that the bird which represents the sun roosts in a mulberry tree. And paper made from mulberry bark wraps offerings in Shinto shrines. That bark is also used to make Tapu cloth in Polynesia. And arrows shot from a mulberry-wood bow reportedly drive away bad spirits.

German folklore on the other hand held mulberries to be evil. Perhaps because of the roots' peculiar color, the devil was believed to shine his shoes with them.

Mulberry leaves can take several different shapes on the same tree. And, although some trees produce just male or just female catkins, others produce both at once. (I'm hoping mine is one of the latter, as I only have a single tree!)

The inch-long fruit can be either black (Morus nigra), white (Morus alba), or red (Morus rubra). Mythology holds that the white berries were originally stained red by the blood of Pyramus and Thisbe. (Those two lovers agreed to rendezvous under a mulberry tree, and Pyramus stabbed himself after he mistakenly believed Thisbe to have been killed by a lion. In "true lover" fashion, she eventually stabbed herself with the same sword.) This story explains why the black mulberry stands for "I will not survive you" in the Language of Flowers.

Mulberries often produce fruit for most of the summer and early fall. That's why it's best to keep the trees well away from the house, as you don't want to be tracking in berry blood for months on end. The fruit is actually a collection of drupes, each drupe having its own seed. So you might say each berry is actually a pod of berries.

As all those silkworms can testify, mulberry leaves are edible. A good source of rutin, they were used by the Romans to treat diseases of the mouth and lungs. In China, they were prescribed for coughs and diabetes, and to encourage sweating or urination. The root bark has been used to expel worms or to produce yellow dye.

Here, we mostly make use of the fruits--in pies, wines, and etc. Like most berries, mulberries are high in antioxidant anthocyanins and Vitamin C, which makes them very good for you. The darker mulberries are reportedly the best tasting, with the white ones being more "insipid." Don't eat any of them raw, however, as they can be somewhat toxic then.

Even if you don't want the berries yourself, the birds will thank you for them. And I suspect it was one of my feathered friends who "planted" my mulberry tree. So they and I will be keeping an expectant eye on it. Who needs silk when you can have succulence?

Morus nigra and alba image is from Phytanthora Iconographia, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden.