Mottled Mountain Laurel

By Audrey Stallsmith

I have been wandering in the lonely valleys

Where mountain laurel grows

And, in among the rocks, and the tall dark pine-trees

The foam of the young bloom flows,

In a riot of rose-white stars, all drenched with the dew-fall,

And musical with the bee,

Let the fog-bound cities over their dead wreaths quarrel.

Wild laurel for me!

"Mountain Laurel" by Alfred Noyes

Since mountain laurel is the flower of my state (Pennsylvania), I decided it was high time I learned more about it. I discovered that the shrub is closely related to the rhododendron about which I just wrote, being also evergreen, poisonous, shade tolerant, and inclined to bloom in late spring or early summer.

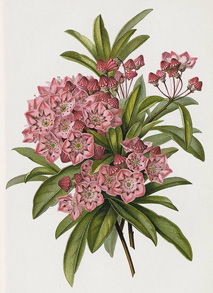

Mountain laurel, though, is native to the eastern U. S. rather than to the Orient. And it shows its independent streak by sporting flowers which resemble tiny bowls rather than trumpets. Those white or pink clustered blooms generally are marked with an exquisite pattern of darker dots or streaks, explaining the nickname “calico bush.”

Linnaeus dubbed the shrub Kalmia latifolia in honor of Pehr (Peter) Kalm. That Finnish scientist—at the request of Linnaeus and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences--visited North America from 1748 to 1751 in search of new plant species. The mountain laurel apparently was one of those he deemed impressive enough to lug back to Europe with him.

Kalm must have greatly enjoyed his adventure, meeting Benjamin Franklin and famed Philadelphia botanist John Bartram and having a whole New World of plants and animals to explore. As if he weren’t already busy enough, the botanist also filled in as pastor for a New Jersey Swedish Lutheran church where the former pastor recently had died—and married that pastor’s widow as well. Thus taking the idea of substitute to a whole new level! (Though Kalm’s parents were Finnish, they were living as refugees in Sweden at the time he was born, so he apparently moved easily between the two cultures.)

In his book, Travels in North America, Kalm writes of mountain laurels that “though they are conspicuous in regard to the colours and shape of their flowers, they are no ways remarkable for smell. . .for they have little or no smell at all.” He also notes what would become a major annoyance for gardeners, that “wild stags” (deer) “eat without any danger the spoon tree, or Kalmia latifolia, which is poison to other animals.” “Spoon tree” refers to the fact that native Americans sometimes carved eating utensils from mountain laurel’s close-grained wood, which colonists also used in the construction of wooden works for clocks.

The shrub generally grows on the edges of mountain forests. So, to keep it happy in the garden, you will need to provide acidic soil, excellent drainage, and a little morning sun.

We can guess that Kalm may have seen, in the plant that stands for “ambition” in the Language of Flowers, the same freshness that he found in a raw new country. And perhaps he would have seconded Noyes’ preference of “Wild laurel for me!”

Kalmia latifolia image is by P. de Longpre from Revue Horticole, courtesy of plantillustrations.org.