Silky Milkweed

By Audrey Stallsmith

The silver-

Haired seed of the milkweed

Comes to rest there, frail

As the halo

Rayed round a candle flame,

A will-o’-the-wisp

Nimbus, or puff

Of cloud-stuff. . .

"Polly’s Tree" by Sylvia Plath

As the poem above indicates, milkweed is almost more popular for its seed silk than for its flowers. That airy fluff, with its waxy waterproof coating, became a lifesaver during World War II when patriotic children gathered millions of pounds of it for use in Mae West life jackets.

“Two bags,” they were admonished, “save one life.” Milkweed silk has also been used to stuff pillows, mattresses, and comforters--as well as papoose cradles and buffalo robes--and is supposed to insulate better than down does.

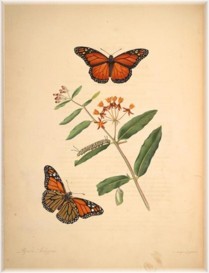

Kids have always loved milkweed for another reason, though, besides the fun of watching that fluff float away. The plant, also known as silkweed, cottonweed, Virginia silk, swallow wort, and—most importantly--butterfly weed, is the host for the Monarch, Queen, and Soldier caterpillars. (Sounds almost like a whole kingdom, doesn't it?)

Countless small fingers have carefully stuffed a piece of dripping milkweed, along with its attached cocoon, into a jar--for the fun of watching one of those glorious butterflies develop and “hatch.” The plant's flowers are also a preferred nectar source for many other "flutter-bys."

The somewhat toxic white sap or “milk” on which the caterpillars feed before their “incubation” makes them distasteful to predators. Although all milkweeds are, as Mrs. Grieve writes in A Modern Herbal, “more or less poisonous,” that toxin is apparently only harmful in large doses to small creatures or children.

My father reports that his family often ate emerging milkweed greens, cooked like dandelions, in the springtime. Their flavor is supposed to be sweeter than dandelion, more similar to asparagus.

Native Americas reportedly consumed almost all parts of the plant, including the sugary flowers, the immature pods—somewhat similar to okra—and those greens. But the fact that milkweed has also been used as an emetic, to induce vomiting, proves that it can be sick-making if you eat too much of it! Birds reportedly often “hack up” those milk-gorged caterpillars.

Although named for the Greek god of medicine, Asclepias, most milkweeds are New World plants. An exception to the rule, Asclepias acida, is native to India. Although we can deduce from its name that its flavor is sour, the plant is highly revered there for its intoxicating properties and identified with the Hindu god, Soma.

There are about a hundred varieties of milkweed. Some of the better known are Asclepias syriaca, which is the common milkweed and not really from Syria; Asclepias incarnata (“flesh-colored”), which is also known as swamp milkweed; Asclepias curassavica (“from Curacao”), which has red and orange flowers and is supposed to repel fleas; and Asclepias tuberosa, which also has orange flowers and is sometimes called pleurisy root. (Because Asclepias tuberosa can help break fevers and is an expectorant—expels mucous—it was sometimes used to treat the lung inflammation known as pleurisy.)

Jethro Kloss recommends common milkweed, along with marshmallow, as a remedy for gallstones. And the plant's sap, which is supposed to contain proteolytic enzymes, has frequently been applied for the removal of warts.

The threads running up milkweed stalks have been used, like flax, to make a kind of muslin or sometimes in papermaking. And the pods can easily be dried for use in bouquets. Or perhaps we can just let that bursting silk remind us to grab onto the last fleeting days of summer before they float away from us!

Plant plate is from The Natural History of the Rarer Lepidopterous Insects of Georgia, by John Abbot, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden Library.