Explosive Clematis

By Audrey Stallsmith

Over the hills and far away

The road is long on a summer’s day;

Dust glares white in the noontide heat,

But the Traveler’s Joy grows strong and sweet,

Down the hollow and up the slope

It binds the hedge with a silken rope.

Graham Tomson—“Vespertilia”

Clematis vitalba, the wild clematis of Britain, grew in roadside hedges. So it came to be known as Traveler’s Joy, perhaps because it provided shade—or even wood--for weary wayfarers. Since its stems crack in flames with an explosive sound, it was also known as atragene or “firecracker.” And its fluffy seedheads inspired the nickname Old Man’s Beard.

The flower’s name derives from the Greek klema (“climber”) and vitalba (“white vine”). The small white blooms of traveler’s joy, however, scarcely resemble the massive and colorful ones we associate with clematis these days.

But hundreds of these species types—250 to 400, depending on whom you believe—grow wild in different parts of the world. When another of them, viticella, was introduced to England either from Spain or Italy, it touched off an initial round of clematis breeding. But it would take a Scotsman named Isaac Anderson-Henry to produce the first larger-flowered type—Reginae--from a cross between patens azurea grandiflora and lanuginosa.

Famous plant collector Robert Fortune discovered the latter species, whose name derives from the Latin for “wool,” in a Chinese churchyard near Ning-po. But it proved both a blessing and a curse to clematis breeders. A blessing because lanuginosa produced very large flowers. But a curse because plants descended from it were much more susceptible to clematis wilt, a fungus disease that causes the vines to wither and blacken almost overnight.

Strangely enough, many of our modern cultivars such as the ubiquitous Jackmanii—a cross between lanuginosa and viticella--were actually produced during the Victorian era. (Viticella is resistant to wilt and free-flowering, which is probably how Jackmanii contrived to thrive and prosper.) After the Victorian period, breeders became so discouraged by the wilt problem that clematis breeding languished for years.

The disease is not necessarily fatal, however, as it doesn’t affect the roots of the plant. So vines that are cut back will often sprout again eventually.

Clematis is a liana, “an upward growing vine with a woody base," and was sometimes also known as “love,” for its clinging ways. It came to represent “artifice” in the Language of Flowers, as beggars used the plant to incite pity. They would rub its acrid leaves on small self-inflicted cuts, to turn them into dreadful-appearing ulcers. One of the best species for this purpose was probably flammula, as its crumpled foliage supposedly smells of smoke and will cause a flashing flame-like pain if sniffed!

In her A Modern Herbal, Mrs. Grieve reports that the crushed leaves of nonclimbing clematis recta will also “irritate the eyes and throat giving rise to a flow of tears and coughing; applied to the skin they produce inflammation and vesication (blisters), hence the name Flammula Jovis (‘Jupiter’s small flame’).

Eventually clematis also came to stand for “mental beauty.” Though why mental, and not physical, is anybody’s guess! At any rate, if planted in conditions it enjoys—“feet in the shade, flowers in the sun”—it can provide one of the most spectacular shows of the summer.

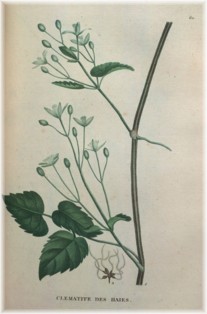

Note: Plant plate is from Traité des arbrisseaux et des arbustes cultivés en France et en pleine, courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Garden Library.